It was 2017, and the future of driving was right around the corner: Fleets of autonomous cars would cruise city streets while self-driving buses swerved around pedestrians. Three years ago, tech companies around the world, including Nvidia and Audi, felt confident enough in AVs to predict this driverless future would be a reality by 2020.

Venture capital funds snapped up self-driving startups, plowing cash into dozens of these companies in China and around the world. Pitchbook figures show the global deal count in the AV sector nearly tripled to 127 in 2017.

Now it’s 2020, and my last rideshare was driven by a plain old human. Global deal count in AVs fell to 96 last year, smaller companies were unable to keep up with the high bar for investment, and China’s government has scaled back its ambitious goals for AVs. Most now realize that it will take years to build autonomous vehicles ready for public adoption.

Drive I/O

Drive I/O is TechNode’s monthly newsletter on the cutting edge of mobility: EVs, AVs, and the companies trying to build them. Available to TechNode Squared members.

The industry had to grow up eventually, and it’s happening now. Small players are leaving the market as it matures around a few success stories; in China, central planners are pushing back targets to match reality. Easier, less flashy applications like delivery-robot autonomous trucks are getting more attention from investors.

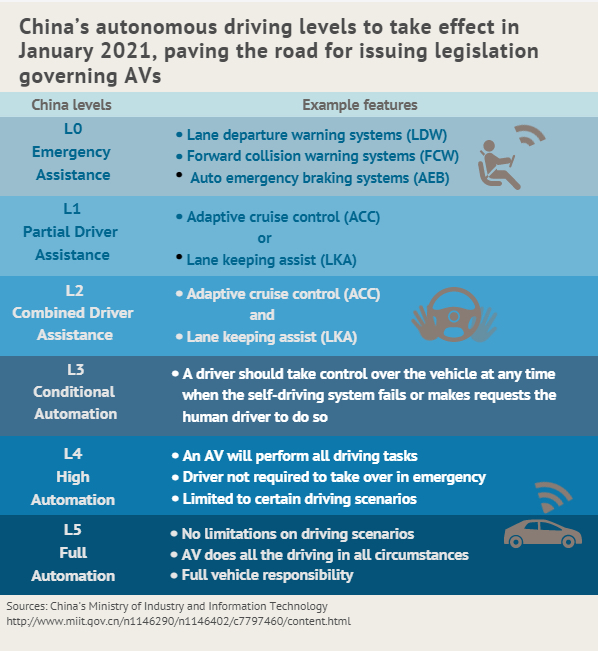

Plenty of engineers are still working on the dream of L5 fully automated cars. But for now, we’d better get used to the existing L2 parking-assist features and L3 office park shuttles.

Q1 AV fundraising

Competition in China’s self-driving market is heating up, driven by a few companies that dominate fundraising.

Only ten Chinese AV startups won investment in the first quarter of 2020, yet these ten startups conquered a third of all investments in 2019, according to an analysis of public records and data from TechNode and Beijing-based consultancy EO Intelligence.

Some of the lesser-known companies winning new war chests claim to control 90% market share in their own domains, a possible sign of maturity among these firms.

As investors realize that the commercialization of AV technology is still a long way off, they are betting larger amounts on more mature companies instead of making smaller investments in a wider range of early-stage startups.

In fact, much of this year’s activity was driven by just two companies: self-driving startup Pony.ai and lidar maker Hesai.

In January, Hesai closed its $173 million Series C, led by German Tier-1 supplier Bosch, among others. A month later, Pony.ai announced it had raised $462 million at a valuation of $3 billion, in what was at the time the biggest-ever funding round in China’s self-driving industry.

Most other companies did not disclose the value of their funding rounds, instead saying they raised “dozens of millions of RMB.” The two exceptions include an autonomous mining startup that claimed to have closed a RMB 100 million ($140,000) round and a delivery robot maker that doubled that number.

China is aligned with global industry trends. Around the world, mobility deal volume and total investment fell while a few late-stage AV companies raised larger sums.

Plans scaled back

A 2017 government plan anticipated that more than half of all cars sold in 2020 would be equipped with autonomous driving functions—but the installment rate of major assistive driving functions on cars was less than 20% in 2019.

Although investors and innovators are rushing to get L3 vehicles on the road, those cars aren’t ready for real traffic conditions. So far, deploying full autonomy means lowering the speed (to roughly under 40 km/hr) and restricting them to a very limited area, which usually means a local community, a school campus, or a park.

“We’re following special-case AVs very closely,” Qi Lei, the investment principal at Alliance Venture, Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi’s global investment organization, told Chinese media. She brought up parks and old people’s homes as being easier sites for robots to navigate safely.

But the problems of getting L3 passenger vehicles on the road were highlighted by Baidu’s 2017 self-driving minibus model, Apolong. With the high price tag of RMB 1.5 million per unit, Apolong’s market performance fell short of expectations last year. Baidu immediately denied the reports with the release of a second-generation model, without revealing sales and cost details. It is unlikely that Apolong is affordable enough to be rolled out widely.

In the latest blueprint released by the National Development and Reform Commission earlier this year, the top economic planner declined to give a specific goal for AV development, instead by saying the country would need to reach “mass production” of intelligent vehicles with conditional automated driving functions by 2025.

Still, another action plan released late last year by China’s industry ministry shed some light on Beijing’s hopes for the AV sector. The report predicted that sales of intelligent and connected cars are expected to constitute 30% of new car sales over the next five years.

“The national guidelines will drive growth in China’s AV industry … facilitating cost reduction and efficiency improvement as the supply chain will move in the same direction,” according to analysts. However, as China currently lacks legislation governing self-driving cars, analysts expect mass adoption of L3 automation of passenger vehicles will probably happen no sooner than 2021.

The government remains confident enough to start writing rules for these future cars. Beijing promises to finish drafting technical standards for commercial vehicles—including those for driver monitoring systems and automated lane changing—by the end of 2020. Research on regulations on driverless passenger transport and unmanned delivery are also among the priorities, indicating that legislation for unmanned vehicles has been put on the table.

Autonomous deliveries

Given the difficulties of building affordable passenger AVs, growing emphasis is now being put on autonomously delivering goods. The COVID-19 pandemic also has driven the need for safe, contactless deliveries.

AV companies are racing to fulfil this niche. Three out of the 10 Chinese AV startups raising funds in Q1 are making robots for grocery delivery, according to TechNode’s analysis of funding data. Meanwhile, six AV companies that secured financing over the past two months claimed that their sensor-based algorithms could facilitate trucking rigs with the capability to drive themselves on Chinese highways.

This trend partially explains why investors have piled into Chinese robot delivery startups during the first three months of this year:

- Uisee, formed by Wu Gansha, a former director at Intel’s laboratory in China, secured an undisclosed amount of fresh funding in February in its Series B from German auto supplier Bosch, among other investors.

- In May, Uisee said its fleet of 75 self-driving cars has driven more than 15,000 km in a pilot project in working with SAIC-GM Wuling, General Motors’ light-vehicle joint venture with Chinese automakers SAIC and Wuling Motors.

- In March, Neolix, a partner of Baidu’s self-driving platform Apollo, announced having closed an RMB 200 million Series A+ led by Chinese electric vehicle maker Li Auto (aka Lixiang) and followed by existing backers including Yunqi Partners.

- In the same month, Beijing-based White Rhino raised an undisclosed amount of funding from Chinese investment firm Estar Capital. The company was formed by a group of former Baidu engineers and transported medical supplies to a makeshift hospital in Wuhan during the outbreak.

Venture funds are also pursuing self-driving trucks for freight deliveries on Chinese highways, as the Chinese government forced the installation of autonomous emergency braking (AEB) systems on commercial vehicles last year.

- In March, Maxieye, a company that claims a market share of nearly 90% in the AEB sector, announced it had closed its Series A from Chinese Tier-1 supplier SORL Auto Parts, without revealing financial details.

- Maxieye said its perception algorithms combining data from a variety of sensors could enable warning and braking based on navigation with merely 1% perception errors from 1 to 50 meters, compared with the 50% error rate achieved by some competitors.

- Soon afterwards, Inceptio revealed a $100 million new war chest from Singapore’s logistics giant GLP, among other investors. The Shanghai-based robotruck startup is pushing forward the mass production of L3 autonomous trucks with partners including Dongfeng Motor, China’s second-biggest automaker, by the end of 2021.

“Innovators and VCs have been through a learning process over the past several years since 2016. We are having a better sense of the fact that there is a very high ceiling to achieve vehicle autonomy—and that the lifecycle either of the technology per se or of the business operation is a lengthy and complex one.”

—Inceptio CEO Julian Ma, speaking to TechNode

Looking ahead, self-driving companies are still among the primary targets for VCs, but the rise of unicorns means more difficulty for early-stage startups to raise capital. “It’s a race with incentive capital over a very long term,” said Ma. As automakers and startups struggle to find nearer-term solutions to monetize their technologies, they’re hoping that regulators will remove the barriers in their path.